In my methods class, we recently read Tina Campt’s Listening to Images. Campt describes her methods in this text as those demonstrating her “commit[ment] to a Black feminist praxis of futurity and the grammar of the future real conditional” or “that which will have had to have happened.”

During our class discussion of this book, my professor mentioned how Western it is to believe that nothing matters. He reminded us how, even while living in some of the bleakest realities, people of the Black diaspora have always had to imagine a future for ourselves.

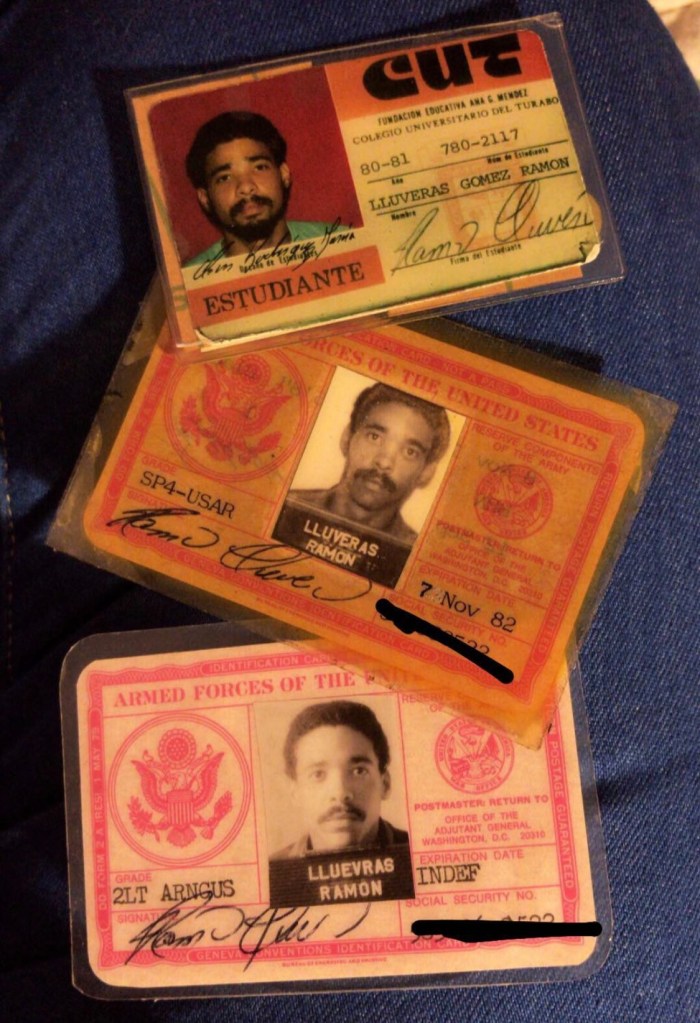

& in this, I was reminded of the difficult decisions the people who came before me had to make because they believed in something better on the other side of the horizon. Like my maternal grandmother who was determined to chase her bag by any means necessary to support the people she loved; like my emancipated paternal bisabuelos who kept bringing babies into the world even as famine and sickness kept stealing their children; like my dad who left his parents, siblings, and mother tongue to cross the Atlantic and make a life here.

How heedless I have been, standing on the shoulders of so many people who had the audacity to dream of a future (and one in which I’ve been the lucky inheritor), to decide to just turn everything off and go lay down because the world as I know it is going to shit.

Today is the 60th anniversary of the founding of the SNCC & so an appropriate time to take stock of the work at hand, to recommit, and to vow to protect my love for the work. I’d like to think this reframe is what Makani Themba meant when she said, “No matter how dark it gets, we must continue to imagine ourselves on the other side of this thing.”