A skill I’m learning late in my life as someone who writes is how to sit with a piece of writing for a while. Usually words pour out of me and within a matter of hours, whatever I’ve written exists out in the world—as a seminar paper, as an op-ed, or (recently) here.

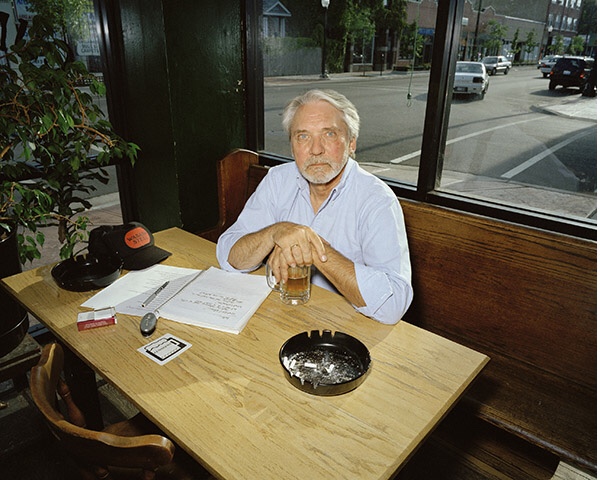

Larry Heinemann was the first person to call me on my shit. Back in 2009 & 2010, I was privileged to earn a seat in his intensive writing seminar at Texas A&M. That he won the 1987 National Book Award came up only once: a classmate of mine said he looked Larry up on Wikipedia & asked if Larry really kept the award’s bronze Louise Nevelson sculpture in his bathroom. “I’ll tell you what I told Michiko Kakutani: Whether I deserved to win or not, the check’s already cashed, the money‘s already spent, & the sculpture is quite comfortable above my toilet.”

Because of my proclivity toward vomiting up whatever writing I owed at the beginning of class just hours before it was due, I was often late to our weekly three hour seminar. On one such day when I came into the seminar an hour and a half into class, Larry asked me what I remembered about my classmate’s writing from the previous week. This was a common exercise at the beginning of the class and after the midway break—meant to call our attention to the kind of descriptions and language that stick, so we could emulate that in our own work. When I gave my response, he asked for another and then another and then another. Much to my classmates’ mortification, seven tense minutes passed in this fashion until I ran out of things I could remember. He asked to meet with me during his office hours that week.

“How was that exercise for you?”

“I think everyone else was much more uncomfortable than I was. I knew I shouldn’t have been so late. I didn’t know you’d be so offended by it, though.”

Larry laughed at my admission. At 22 (& sometimes still at 33), I was both, oblivious & an ass hole; a malicious cross section. What he said next could have been a lie meant to motivate me, but it was also kind:

“You owe it to yourself to be here on time. Your writing is too good for you to not take what this class can offer you seriously.”

Once, Larry selected one of my short stories to read out loud. It was about a recurring dream I’d had ever since I was a kid. The dream starts with something that happened in my waking life when I was four or five—a group of butterflies flew into my open bedroom window and landed on a brightly colored blanket. I didn’t understand what they were and I was afraid of them. So I walked over to the place where the group of butterflies was fluttering, folded the blanket over them, and smashed them. My brother came into my room to see why I was screaming and I told him there were flying things in the blanket. When he pulled the blanket back, he was sad at what he saw.

“Lauren, those are butterflies. They’re nice. And they’re pretty. See? Look at how pretty they were.”

I examined the crushed blue, orange, and pale yellow wings in the blanket. They were very pretty now that they were still. My brother carried the blanket over to my open window and shook the dead butterflies free. At that time, we lived on the top floor of an Army barracks in Frankfurt, Germany. I watched the butterflies fall from the window—it seemed like it took forever for them to reach the ground because they were nearly weightless.

“You’re not supposed to kill those,” my brother said, leaving me at the window realizing what I’d done. For two decades thereafter, I regularly dreamed about that moment. In my dreams, I’d climb out of the window and fall with the crushed butterflies. As I fell, I’d pass through a rainbow.

“That story is about suicide,” Larry told me once. It seemed a strange reading to me then, but who was I to argue? Maybe it was. I don’t know whether he realized it—it took me many years after that to realize it myself—but in that moment, Larry gave me the permission to write about my sadness. It was a permission I sorely needed.

I’d like to say I was never late to Larry’s seminar again after that, but it isn’t true. I just took care to be less late. But I did learn to start writing things sooner and to take my time with my writing. For Larry, that was good enough.

Larry Heinemann was the kind of professor who would smoke cigarettes with students during the class break. At the end of the spring semester, he took us all out to a small bar around the corner. It was karaoke night & he bought the first round of drinks. We all agreed to sing at least one song, and when it was his turn, Larry asked the host to play the Woodstock recording of Jimi Hendrix’s playing the Star Spangled Banner. A version that is lyric-less. For the ensuing four minutes, Larry stood on stage, pretending to violently whip around an American flag.

My colleague, Zalika Ibaorimi, was tweeting today about haunting, which made me think of Larry.

Larry may have been the first haunted person I ever knew personally. He and two of his two brothers were drafted during the Vietnam War and, though he rarely talked about his time there (save for his stories about returning back to the US where, as they were taken through the country on a long and arduous bus ride, the soldiers were encouraged to pass the time sleeping and taking barbiturates), three of the four books Larry wrote were about Vietnam.

In class, Larry told us that Paco’s Story, the book for which he controversially won the national book award in 1987 (over Toni Morrison’s Beloved), was about an American soldier who returns from Vietnam and gets a job washing dishes. The part he left out for us is that Paco is haunted throughout the novel by his fellow soldiers who did not survive the war.

During the lockdown, I thought of Larry and looked him up on Facebook. His page had been converted to a remembering page—a feature for accounts belonging to people who have passed. I thought it must have been a mistake and I googled Larry. He passed away on December 11, 2019.

Reading the many eulogies and profiles about Larry, I learned (somewhere though I can’t find it now) that one of his brothers was among those who died in Vietnam. Another of his brothers returned to the United States only to go missing sometime later. One of Larry’s quotes about Vietnam stuck with me and opened up so much about my memories of him:

“The war has been like a nail in my head, like a corpse in my house and I wanted it out, but for the longest time now, I have had the unshakable, melancholy understanding that the war will always be vividly present in me, a literal, physical, palpable sensation.”

Though he was haunted, Larry’s favorite stories he shared with us were about drinking shots in Vietnam after he’d returned as a Guggenheim fellow decades later—he often went for bottles with snakes or bear fetuses preserved in the alcohol. Another favorite were stories about watching his wife give birth in their marital bed. Larry loved to laugh and he had a dry sense of humor. When we’d read our work out loud in class, he’d tell us, “let go of your voice.” I didn’t know then what that meant, and sometimes I’m still not sure I understand, but every once in a while, as I’m reading to myself I still hear those words.