Last weekend, Gabe and I joined a group of friends online for a few rounds of Among Us. Truth be told, though we played for at least two hours, there are still quite a few rules in Among Us that escape me–but I did have a moment where something about the game felt vaguely familiar. Today, when the Puerto Rican Studies Association put out their statement on Natasha Lycia Ora Bannan, I realized that (the so-called) area studies can sometimes feel a lot like a game of Among Us: many of us hoping to build coalition, some of us trying to snuff out imposters, and still others trying to convince the group that we’re the real deal. Unfortunately, the area studies are often riddled with people who absolutely have valuable insight and contributions, but who are performing ethnic, racial, and national identities that they haven’t inherited organically–making it such that no one engages in Among Us protocol for the sake of it, but because real and finite resources are implicated.

I started writing this personal essay in the fall of 2020, when Jessica Krug posted her now infamous letter on Medium in which she admitted that for several years, she pretended to be an Afro Puerto Rican woman (“an unrepentant child of the hood”) from New York, while actually being a white woman from the midwest. Such interloper stories seem to be rampant since the days of Rachel Dolezal: Sean King, Hache Carrillo, Krug, CV Vitolo-Haddad and most recently, Ora Bannan.

My motives for writing and sharing this story have evolved over time. In earnest, earlier iterations of this essay sought to provide evidence should I ever be in the position of seeming (to borrow yet again from Among Us) “sus”–in lieu of stapling family photos to my forehead. But having sat with different versions of this essay for so long and witnessing different sides of the discourse–who can do what work? who can claim which identities? who is really Black or Indigenous? what do we mean when we use phrases like BIPOC?–I felt that this was an opportunity to share my perspective on some of these questions through the lens of my own family experience. To my mind, there is no better place to begin than with The Story.

All of my friends have heard The Story—nearly twenty years since, I’m still so mortified by it that I feel compelled to share it almost compulsorily.

No sooner had my father and I stepped off a plane in San Juan and picked up our rental car than we headed to a nearby hospital to sit at my grandfather’s deathbed where, after years of battling with alcoholism, he was dying of complications from a failed liver.

It was the summer of 2002 and I barely knew the man whom we affectionately regarded as Papa Moncho. For much of my life until this point, my grandparents lived on separate floors of the same house and whenever I visited them in Puerto Rico, I stayed upstairs with my grandma. Sometimes, my mom would take me downstairs to Papa Moncho’s floor. He was often drunk, quiet, and sleepy. When we arrived on his floor of the family home, he’d put the Simpson’s in Spanish on his television for me before returning to his recliner, which was always guarded by a paper cup full of brown water and cigarette butts. My mom would rub Papa Moncho’s temples and talk softly to him, though I don’t remember him saying much back. Every so often, I’d go downstairs to his house alone out of curiosity. Usually, I’d find him sleeping in his room and sometimes I would lay down beside him and stare at his sleeping face, hoping he’d wake up and smile at me. I can’t remember a single conversation with him, or even the sound of his voice, save for the brief exchange we had in his hospital room the afternoon we arrived in San Juan.

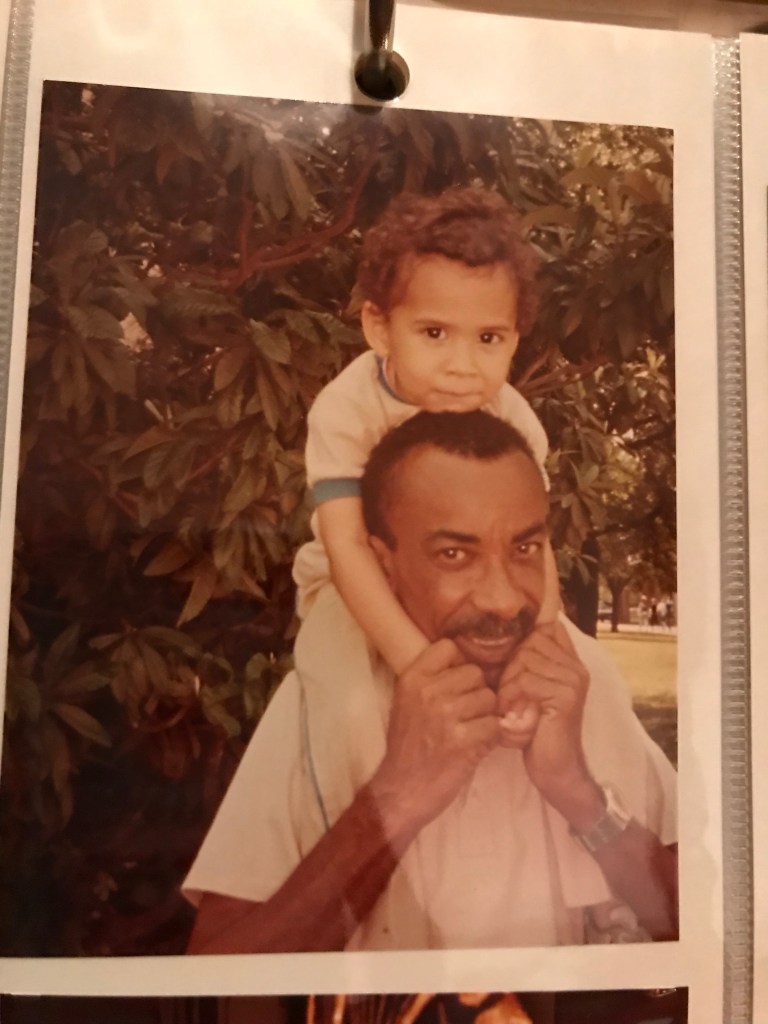

I remember only fragments from that time: it was a characteristically humid day in Puerto Rico and as we arrived at Papa Moncho’s hospital bed, my dad’s brother was in and out of the room (I think he worked at that hospital), while my cousin, Ivy, was running the back of her cinnamon brown hand across my grandfather’s forehead.

At fourteen, I was very big into having straight hair. Before I got into the habit of keeping it straightened, people would call my hair “coarse,” “frizzy,” and “bushy.” A particularly popular thing one of my childhood classmates said to me was, “What do you use to cut your hair? A bushwhack?” And even other Puerto Rican adults would sometimes tell me that my hair was too coarse for me to be a real Puerto Rican.

Much as I reported all of this teasing to my parents, they never validated me—my dad would say my “bad” hair was his fault and apologize (something I didn’t understand then). More often than not, my mom was yet another source of teasing: when I was nine, she tried to straighten my hair on an ironing board with an iron—the way she learned to tame the large waves in her hair during the sixties. When this method failed to replicate the same results for my hair, she took me into the bathroom, produced the scissors from her sewing kit, and chopped my hair off, up to my ears.

“Now we don’t have to spend so much time fighting with that ratty mess,” she announced.

I was devastated.

After my hair grew back and after more tearful evenings recounting the things my classmates said about my hair, my parents arrived at a solution: I should get my hair relaxed. The teasing was replaced by well-meaning comments: in the same breath that she told my classmate how much she liked the blonde ringlets resulting from her recent perm, my sixth grade history teacher told me “your hair is so silky now! You used to look like a jungle woman!”

So I should have felt something like relief when my grandfather looked at me—really looked at me for the only time I can remember in my whole life—and put a weak hand into my long, straight hair. He seemed pleased and managed through a strained voice to say, “ella esta mejorando la raza.”

On the ride to my grandmother’s house that night, I asked my dad what that meant—mejorando la raza—& my dad told me it means “to straighten out (i.e. better) the race.”

Papa Moncho was unambiguously Black; his skin was the rich brown of loam and coffee grounds. He was born to parents who were among the first generation in their families who were not enslaved but born free (it’s worth noting here that Puerto Rico was slow to abolish slavery: though the Spanish Assembly voted to end slavery in 1873, the agreement conditioned that the enslaved would continue having their labor stolen from them for an additional three years). My Papa Moncho married someone lighter, believing in the benefits of proximity to whiteness, & so did my dad (lighter still after my parents’ divorce, in fact).

Two years before this trip, when I was in the sixth grade and when the red-headed, wrangler wearing, and sun burnt object of my affections, Travis Price, rejected me and suggested a list of boys (all Black) who could be my boyfriend, I went to my dad in confusion. He told me that even though I didn’t understand it yet, I was a “jewel” to Black men but that I had an imperative—a duty from Papa Moncho—to marry someone lighter so my children could be lighter.

In spite of this urging, at fourteen and riding away from the hospital, I still didn’t understand.

“Better the race, how?”

“Because your skin is beautiful and light and your hair can be so straight and pretty.”

Racism, colonialism, and imperialism—in addition to being violent, transgressive, exploitative, and extractive—has left diasporic people with warped senses of self. So I try to look at my parents’ decisions—to raise us away from our family; to encourage our marrying as close to white as possible; to tell us to straighten our hair and stay out of the sun; to not teach us their mother language; and to raise us as “Americans” first—in the light of what these measures were meant to be: protective. These are the ways they understood the world to be safer, and the rules by which they understood success as something that could be achieved (and worth achieving, even at the high cost of distancing yourself from your family, nation, culture, and language). To them, the rules of success were simple: white is right.

Which isn’t to say I agree with them–in fact, I’ve vehemently opposed this ideology within my family at great personal expense. But, I understand their choices to have taken place within the vacuum of anti-Blackness and know that robust traditions of passing and racial cleansing exist among Black and otherwise dark-skinned people globally. In her book A Chosen Exile, Allyson Hobbs states that passing for white required not just actions on behalf of the person choosing to pass, but for many, required omissions and silences from their family. Hobbs states that more than a phenotype, Blackness is perceived based on a person’s relationships with other Black people. My parents’ choices to distance themselves from other Black and Indigenous people was contingent on their belief that by leaving behind these social relationships, they could distance themselves from being perceived as Black and Indigenous–allowing them access the privileges afforded “non-raced” (i.e. white) people.

It didn’t pay off. Not only did my parents continue to experience racism based on their phenotypes, but I have to assume there were times when they felt lonely. I certainly felt lonely. I was often left out of my white schoolmates’ social gatherings & it seemed that my white friends’ parents eagerly sought reasons to keep me out of their houses. I wanted the community of cousins I had in Puerto Rico. I wanted to understand the Sunday school games and songs at my grandmother’s church. I wanted to be one of the young Puerto Rican girls swaying her hips as she walked to the store, knowing her handsome crush was watching from his apartment balcony (really, all of us were transfixed and we too looked on from our yards and patios while savoring the breezy early evening air). I loved the pink and teal mid-century modern homes on my grandma’s block, the wild roosters, the crisper full of mangoes in my grandma’s fridge. I wanted all of these delights for myself such that though (to his mind) my grandfather’s comment was meant to be a compliment, it broke my heart: I felt as though it solidified that I didn’t belong in this place that I wanted to belong to, and that I was not of the people I wanted most to be with.