The night before Papa Moncho passed, I slept at my grandmother’s house without either of my parents for the first time. I was laying awake thinking about the hot air, the humidity and the chirping coquis, and still turning over what my grandfather said to me when my Titi Wanda came into my room and laid down beside me. She told me that when she and my uncle were kids, they were so ashamed of Papa Moncho’s dark skin they wouldn’t walk with him in public. My dad was the only one who didn’t care if people saw him with his father. Recalling it now, I think she was offering me an apology for what Papa Moncho said at the hospital, but at fourteen, I didn’t connect the dots. That night, my Titi Wanda stayed in my room whispering stories to me about my Papa Moncho until I dozed off. The only one I can remember is about his bunny, Peaches.

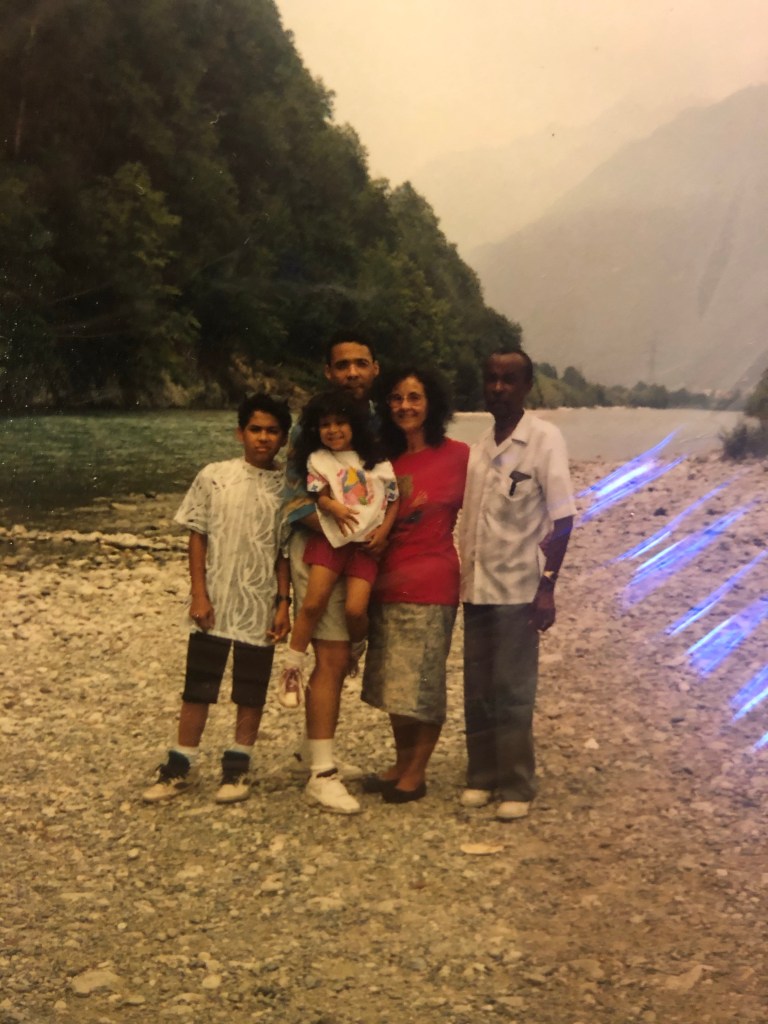

All of this time later, that story is still something I hold onto and try to mine for clues about what my Papa Moncho was like before he became sick. Though it deviates from the arc of this essay, this story about this time feels incomplete without it. In the mid-fifties, my grandparents moved to the Bronx together and sent remittances back to Puerto Rico for their family to save on their behalf. They hoped to come back and use their savings to buy a house. But this time in Puerto Rico was a particular period of exploitation, so their family didn’t save the money—instead spending it to meet their monthly needs. When my grandparents, my dad, and his siblings returned to the archipelago, they had to move into a basement apartment at the top of Gurabo’s infamous hills.

Over time, bit by bit, they built the house my grandmother stills lives in to this day. Now that he had his own backyard, Papa Moncho decided one way he’d provide for his family was to raise rabbits for food. The first group of rabbits he bought all came and went, except one—an apricot colored bunny who he named Peaches. Over many years and many different cohorts of new rabbits, Peaches was the only one to receive a name and the only one to avoid becoming a fricassee spooned over rice and kidney beans. It was unspoken but understood in the family that Peaches was Papa Moncho’s pet. One afternoon, when my Titi Wanda was doing her chore of feeding the rabbits, she noticed Peaches was gone. She went into the kitchen to ask what happened to Peaches & my grandfather indicated toward a caldero brimming with stew. Later, my grandmother told Wanda that while trying to bestow a special treat upon Peaches earlier in the day, Peaches bit Papa Moncho. And so came the end of Peaches’ good run.

I fell asleep that night in May 2002 thinking about how my Papa Moncho was a decisive man, a man who wanted to provide for his wife and children, a man not to be wronged, and—the thing I hold most precious from the story—the sort of man who came to the United States, saw a pile of fuzzy, pink peaches at the grocery store for the first time, and must have asked someone what they were. He was the kind of man who remembered this English word and later, seeing a fuzzy, pink rabbit in a pack he intended to raise for food, thought of sweet, ripe peaches in New York and decided that was this bunny’s name. Though I may not have many memories of my Papa Moncho, I do know he was the kind of man who named a bunny Peaches.

Papa Moncho passed away the next morning while my dad was changing clothes. Having spent the night at Papa Moncho’s bedside, the way my dad came into my grandmother’s house, hurried through a shower and rushed to get dressed has stayed with me for so many years. So, too, has the image of my father—shirt yet unbuttoned and doubled over in pain—as he heard over the phone that Papa Moncho had gone.

Walking in public with your Black father is one thing, but coming away from your Black parents’ anti-Black world lens unscathed is another: I know I haven’t. And still, I was floored by my dad’s reaction when I called him to talk about Dr. Jessica Krug.

Krug is a white woman from Kansas who became a tenured-track professor of Africana Studies at George Washington University. Though there are plenty of white Africana Studies scholars who make critical and crucial contributions to the field, Krug thought it necessary to pretend to be a Black Puerto Rican woman from the Bronx who’s parents were drug addicts.

Krug’s faux identity is parallel to my real one: I am a Black Puerto Rican, and on both sides of my family, lives have been torn apart by addiction. My maternal grandmother was in and out of prison for most of her life for dealing, prostitution, and notably, cop killing. As outlined earlier, my paternal grandfather eventually succumbed to the effects of chronic alcoholism. When I’m being honest, I can admit there were difficult chapters of my life where I, too, dabbled in self medicating. Though I did not grow up in the Bronx, I have always lived in working class, Black communities—most notably, Killeen, Texas, where I lived for twelve years between the ages of 7 & 19.

In light of all the ways that my parents intentionally created distance between us and our culture, language, and community—engineering loneliness so that we might be successful—I feel angry to have my identity rendered costume and performance by someone who hasn’t experienced that loneliness first hand.

I expected my dad would feel the same way, but to my horror, he repeated the rules of the game to me:

“She’s smart, she knew she was competing in a smaller pool and that because she was cute (read: light skinned with wavy hair), she could be a standout.”

“Doesn’t it make you mad that she took opportunities away from people like you and I?”

“No, it makes me happy to know you have those opportunities. You know now that because you’re *cute* ( i.e. light with curly hair), you can win all the same prestigious awards. Of course it’s a problem that *this* (colorism) is a determining factor in Black groups, but these have always been the rules of the game, so now you just have to play.”

I wanted to cry.

Further into the conversation, when my dad repudiated his own Blackness and said, “I’m not Black, I’m Puerto Rican.” I did cry.