Here is a place where I have the privilege of disagreeing with myself. In 2018, I wrote an op-ed entitled something like, “Is this the year Latino Americans unite?” In that essay, I argued that in the face of the Trump administration’s targeted cruelty toward so-called Latinos, the diverse populations housed under this ethnic umbrella had an opportunity to mobilize as a cohesive force.

In the years since, and largely through witnessing a lack of class and racial solidarity among Latinos in response to the Trump administration’s vilification, I’ve divested from the project of latinidad. Originally thought of as a political project of building coalition across diverse populations in the Caribbean and Americas, I’ve come to regard latinidad, like mestizaje, as a white supremacist project where the needs and ambitions of the darkest and poorest are sacrificed for the lightest and wealthiest.

“If you aren’t Black, what are you?” I asked my dad through tears.

“I’m jabao.”

Across the Americas, words designating a person’s blood quantum—that is, a person’s fractal relationships to and distance from Blackness—took hold. In the (predominantly Southern) United States, we know these designations as quadroon, octaroon, mulatto, etc. But such designations appeared everywhere Black people were brought in bondage. Jabao, the label my father claimed in our conversation, is such a word. In Puerto Rico and elsewhere in the Spanish speaking Caribbean, this word was used to classify people who were light complected with otherwise phenotypically Black features.

My dad’s decision to hide behind his blood quantum designation is common among plenty of people who come from the Caribbean and Americas. It’s also precisely why I, myself, have chosen to depart from latinidad. In multiple ways, latinidad has proven itself an anti-Black project. In a recent review of Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents by Isabel Wilkerson, published in The London Review of Books, Hazel V. Carby wrote:

“The trade in commodified human beings was, however, integral to a global, not national, project of colonial modernity. As African and Indigenous peoples were dispossessed and subjugated, a multiplicity of complex, entangled racial formations were created across the Americas. The black national narrative has come to dominate the popular and academic imagination in the US, mirroring the theory of American exceptionalism and separating the history of African Americans from the histories of the descendants of other survivors of the crossing. The plural geopolitical concept of ‘the Americas’ is rendered meaningless when the US is seen as America rather than a region within America, and the history of its black population treated as definitive of a black experience separate from the histories of the peoples oppressed, displaced and eradicated by settler colonialism and its aftermath.”

When I say I’m Black, I’m not ignoring the obvious fact of my multiracial and multiethnic identity but rejecting blood quantum, which is eugenicist and anti-Black. When I reject latinidad, it’s not because I’m pretending that my identity doesn’t lie with people throughout the Caribbean and Americas who were colonized by the Spanish, but because I’m embracing that Blackness is as prevalent among these colonial subjects as it is in the US. In other words, I don’t find latinidad useful for explaining a phenomenon that speaks for itself. I believe I can acknowledge that I’m Black, multiracial and multiethnic without reifying harmful frameworks like blood quantum, and without participating in the falsehood of mono-racial identity.

At this point, I think it’s critical that I address the elephant in our metaphorical room. There are apt to be those among you, dear reader, who have made it to this third and final installment of this essay by taking occasional pauses to roll your eyes: “wah wah wah, you’re light skinned: the world is so unfair in spite of the fact that the gaps between home ownership and wealth among light and dark Black people is wider than it is between Black people and white people. Poor you!” I hear you. This isn’t one of those stories, allow me to get there.

In November, I interviewed Shayla Lawson about her book, THIS IS MAJOR. One thing I really appreciated about her book and about the conversation we had was her insight on this topic. Her book introduced me to the Fitzpatrick Scale and, as she pointed out during our talk, we know that Black people exist across every range on the Fitzpatrick Scale. Which isn’t to say that we should do away with phenotypic Blackness but that phenotype shouldn’t be our only metric for determining whether someone is or isn’t Black. Rather, Lawson proposed that instead of focusing our energies on whether there are modal and deviant forms of Blackness, we should simply resolve to center and uplift the darkest among us because anti-Blackness is, at its very foundation, predicated on the supposed inferiority of people with dark skin.

Here we come to our elephant.

Not only had Krug’s deception hit me on the level of “how dare you turn me into a caricature?” but through my dad’s words, I realized Krug’s story resonated at the level of one of my deepest insecurities: I feel like a fraud. I feel like a fraud for not being darker, for not speaking Spanish, for having no rhythm, for not growing up poor, and for never having lived in Puerto Rico. And this feeling of being a fake is a wound that never scabs: no fellowship, no award, and no job has ever made me feel any less of a fraud, but instead, has always made me question whether I deserve any of it. I am not the stand out student from AADS cohort 7, but still found myself the lucky recipient of the department’s outstanding graduate student award for 2020; I was hired at a local Black nonprofit with a lean staff; I have been granted a TA’ship every semester of my graduate program; and this academic year, became an AAU fellow with a placement in the university’s Black diaspora archive. My CV is thicc and where I’m not the most outstanding, hardest working, or most brilliant person in my department, admittedly I am among the lightest. When Krug pulled back the curtain on her minstrel show, I felt exposed: if she could earn entry into all the spaces she has by pretending to be someone like me, what does it say about people actually like me in these spaces? What if my hot girl CV is less a product of merit and more so a scathing demonstration that (my) proximity to whiteness is an institutional VIP pass?

After my jarring conversation with my dad, I recounted all of this to my partner, sparing no details (to his chagrin, I’m sure).

Multi-generationally from rural Georgia, Gabe’s bronze skin, high cheek bones, and coily hair are often regarded with suspicion in the form of, “what are you mixed with?” and “Where are you *from* from?”

Notwithstanding the commonalities between our raced and gendered experiences of living in ambiguously Black bodies, one of our major points of departure is our respective understandings of how Blackness functions globally. There is no right answer to this question but where I’ve approached it from a diasporic, pan-African place, Gabe’s Black is grounded in the United States.

“It has to be—everyone else in the world can say they are something else. They can hide behind all the different things they are: Jamaican, Nigerian, Honduran, Cuban. We have to be Black, and they think they are better than us.”

I’ve pushed back on this statement a hundred times, but here was the very sentiment Gabe described playing out in my own life. My father’s words felt like being spit on.

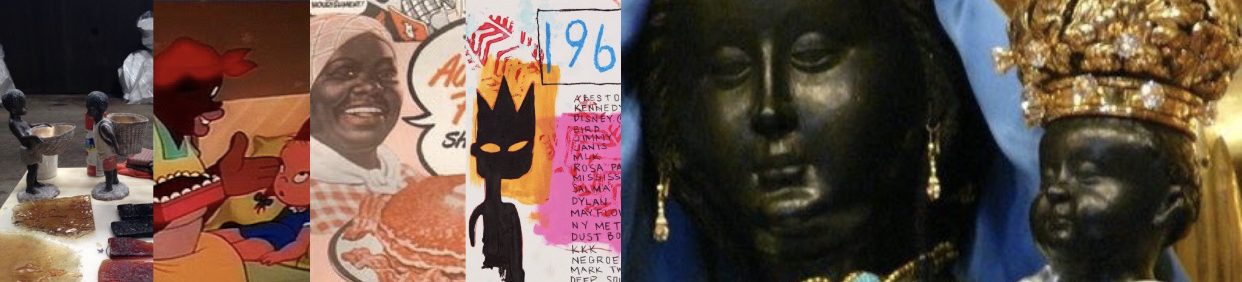

Part of me expected that Gabe might gloat: he’d been proven right in an argument that snakes through the arc of our relationship. But instead, he offered me a reframe: what if instead of feeling exposed, I thought of Krug and my family’s histories as lenses for my own research? How are gendered, colorist, and racialized stereotypes materialized in Caribbean faith practices? How do these manifestations represent ruptures and departures from how Black people in the US regard and take meaning from the same symbols?

What Gabe poignantly offered me about my research is something that only he could, but even more invaluable to me was that he sensed what I needed and gave me that, too. Though I’ve historically been the person to default in arguments to, “two things can be true,” here, Gabe said that I must hold both of these things: I can be good AND it’s true that I benefit from looking as I do and having an ethnic identity grounded in the Caribbean (which of course, reads as exotic and, therefore, preferable in the logics of white supremacy).

In fact, these things have to co-exist—I don’t get to choose whether or not I receive privilege from being light and evidently multiracial. But in acknowledging this, it frees me to move differently: in holding an awareness of my relative privileges in Black spaces and in spaces where darker Black people might otherwise be excluded, I don’t have to replicate colorist hierarchies. I can use my entrance in these places to create space for dark skinned people, and particularly, dark skinned women. I can make sure that hiring and recommendation processes I’m apart of advance phenotypically Black candidates. I can advocate for my darker peers and friends and make sure that for every opportunity I’m allowed, I bring twice as many unambiguously Black people along with me. Beyond my research, I’ve come to regard this as a critical part of my life’s work. The work doesn’t end with confession and acknowledgement, but these lay bare the ways I must utilize my privilege to materially and tangibly fight anti-Blackness. Last year gave me the opportunity to put my money where my mouth is: through the money I earned from my award and my on as well as off-campus work, I’ve been able to reallocate at least 25% to mutual aid and to darker skinned peers struggling with moving expenses, family emergencies, and health crises.

To return to my earlier analogy between Among Us and area studies: I believe all of us who are invested in the project of Black liberation should arrive at the same place such that we know imposters not by their phenotypes and cracks in their performances but by their refusal to uplift dark skinned Black people.